Coherence Front to Back Key to Usable Impact Statements

Research proposals to all kinds of funders are now expected to set out, in glorious detail, how they will create societal impact from their research results. But research proposals are in reality promises of future activity and thus extremely hard to judge. How can evaluators best select those proposals that have the greatest chance of delivering on that promised impact? To address this problem, rather than attempting to predict the future, we have developed a framework for evaluating the way in which research proposals commit their participants to creating particular kinds usable knowledge.

Evaluation plays an important role in scientists’ lives. When done well, research evaluation provides a ‘glue’ that holds science together as a collective endeavor pursuing “good” choices. Evaluation signals ‘good research’ and researcher credibility, which in turn indicates to other scientists which ideas should be accepted by the community and which papers should be read. The overall effect steers scientific communities towards answering the most important questions. However, research evaluation does not just address ‘good science’: scientists are increasingly evaluated on their research’s societal impact, thereby adding evaluation signals from a wider pool of non-academic participants. Impact evaluations therefore create an additional dimension to scientific credibility and what constitutes ‘good science’.

Whereas, research impact can be assessed and understood ‘ex post,’ or after the fact in a variety of ways (we have previously proposed a framework of 13 different pathways to research impact). Performing ‘ex ante’ assessments, before the fact, as many funders require is more complex. It also arguably has more influence in steering research towards particular goals, as it is important in determining which researchers receive funding and hence opportunities for undertaking research, generating results, presenting at conferences and publishing in journals. The rise of impact evaluation in proposals therefore effects what is regarded as ‘good science.’ How can evaluators meaningfully distinguish implausible claims from the credible and ensure that ‘good impact’ is encouraged and rewarded?

We judge proposals in their scientific credibility through looking at what we consider as two characteristics: “activity coherence” and “project coherence.”

- Activity coherence is the way that a single element of the proposal (e.g. literature review) fits logically with existing scientific knowledge and uses that knowledge in a consistent way e.g. to propose a model?

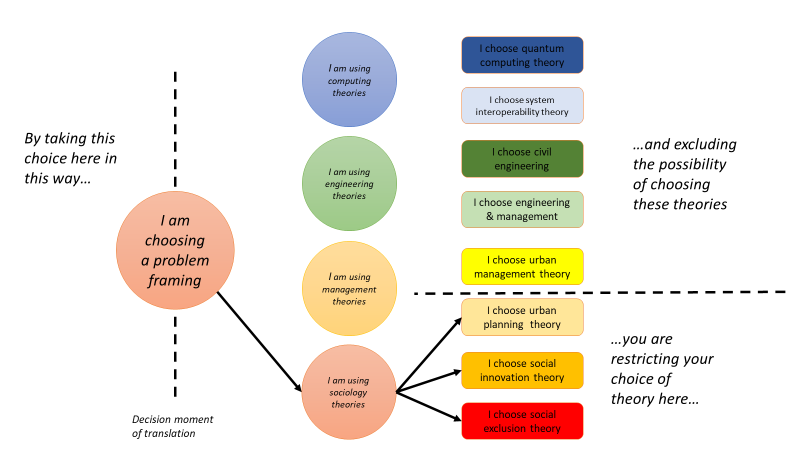

- Project coherence is the way that the various individual elements are consistent between them: e.g., if a proposal frames a problem in sociological terms, then we expect the literature to propose a sociological theory and not to choose an engineering approach (see figure below).

The figure below illustrates the choice that exists in the framing of a proposal around “smart cities,” the use of artificial intelligence and ubiquitous computing to improve urban management. Before the choice is taken, the academic could potentially choose to frame the particular issue as a computing, infrastructure, organization or social problem. But when that frame is chosen, it constrains the later choices: choosing a sociological frame limits the coherent next choice to a restricted range of theories. It would most likely be incoherent to frame the problem as sociological and then propose a computer science framework to address it.

These two characteristics are interdependent, the need to be consistent between project elements means that early decisions regarding the scientific literature, will have a binding effect upon later activities in the proposal. Consistency across these factors enhances the credibility of claims that the knowledge produced will make a contribution to the field.

This principle of binding may be applied to judging the credibility of impact creation. Drawing upon an argument we developed at greater length in a previous blogpost, we argue impact emerges from usable knowledge; what makes knowledge usable, is the way that it depends on user knowledge. Although one can never know with certainty whether users will make use of research findings, usable knowledge has a greater propensity to be used and as such impact.

A project initially framed by a user question may be tightly committed to produce knowledge that answers that user question. Likewise, if the method involves users in data gathering, building on context-specific user knowledge, the resultant analysis will be cognate with societal partners’ knowledge, thereby increasing usability.

Credible impact statements are those that capture this, by showing that they draw on users’ knowledge in early research stages in a coherent way (activity coherence), thus creating dependencies on user’s knowledge in the later stages (project coherence). By considering both signals of (a) activity coherence, and (b) project coherence, evaluators can better adjudge how far a proposal is committed to creating usable knowledge.

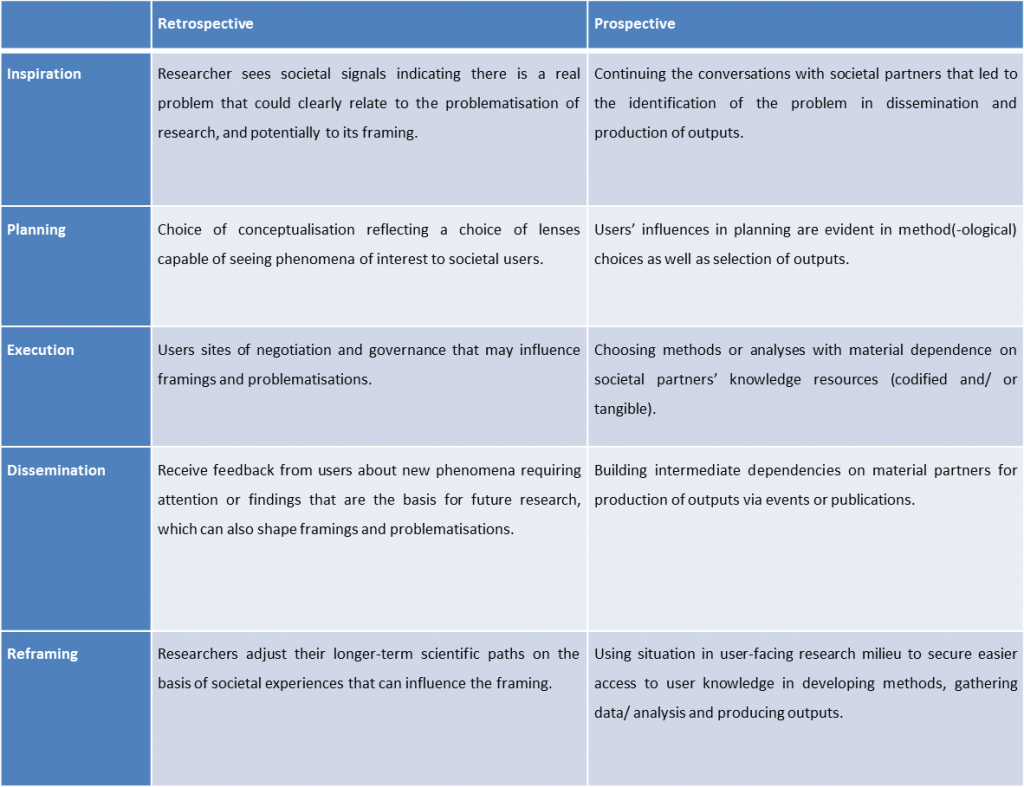

A proposal at the time of writing has typically already fixed a framing, problematization and conceptualization, whilst method, analysis and the generation of arguments may be stated, they can always be changed later if need be. The figure below shows how those choices may strongly or weakly constrain projects to creating usable knowledge.

In this table, we set out the ways in which these kinds of commitment may be signaled. The evaluation challenge is judging how far they firmly bind or softly steer researchers towards creating usable knowledge.

Our framework suggests that a fundamental rethink is required in ex ante impact evaluation, ensuring the most impactful researchers are given opportunities to shape how we define what constitutes research. The benefits of such approaches would allow research resources to flow to proposals that make the most compelling cases that they will create impact, not those proposals that make the most eye-catching claims of potential impact. What is necessary to achieve this change are two steps. Firstly funders and reviewers should accept the need for a more logical approach to reviewing impact. Secondly, researchers and funders can help identify and clarify the ways in which proposals serve to bind research practices to particular outcomes.