LSE Impact: Social Science in a Time of Social Distancing

[Ed. Note: Michael Taster is the managing editor of the LSE Impact of Social Science blog and posted this opinion piece there today.]

The spread of the COVID-19 virus has presented an unparalleled challenge for society, academia and the social sciences. As universities across the UK and the world have halted teaching activities, closed campuses and moved to online forms of working, major changes have been asked of individuals and society as a whole. As of last week, the LSE Impact blog has shifted to remote working, a transition, which many others fortunate enough to be able to will also be making. Whilst the medical and scientific establishment have mobilized to respond to the outbreak, discussions around how social science will both impact and be impacted by COVID-19 have been more muted and often secondary to scientific concerns, yet they remain, now more than ever, necessary.

The impact of social science

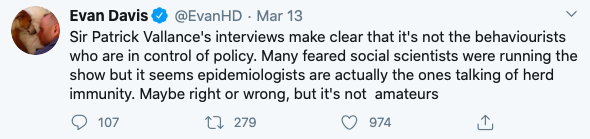

There is little doubt that an effective response to COVID-19 will require social scientific expertise. As with previous epidemics, such as Ebola, social science research and expertise have proven invaluable in combating infectious diseases and contributing to epidemiology and public health, which are themselves both examples of multidisciplinary fields that from their inception have been strongly influenced by a wide range of social science disciplines. However, at least in the context of the UK, there has been a degree of backlash against the idea that social scientists might be integral to responding to COVID-19.

Setting aside these particular criticisms and the question of who might count as a professional, COVID-19 has already presented itself as a deeply social issue. Public health measures taken to prevent the spread of the virus, from handwashing, self-isolation to city lockdowns, all require insights from social research if they are to be effective.

However, beyond public health, the wider spillover effects of these measures present unique social challenges. The massive interventions currently being made into national economies, urban systems and social welfare to support people in a time of crisis will ultimately draw on the knowledge and expertise of those who have studied how these systems work in more normal circumstances. The effects of social distancing on families, education and psychological well-being pose yet more challenges for social researchers. Even the way in which information about the virus is communicated, is again a key area in which social research can make real contributions. In all these areas and more, social science has an important role to play, by directly contributing to policy, but also by acting as a critical friend, which raises the urgent question: how can this wealth of knowledge and expertise best be communicated?

Communicating social science

As was made apparent recently by the release of research modelling the impact of the virus by professor Neil Ferguson and Imperial College’s MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis, uncertain conditions in which decisions have to be made require expert inputs and can lead to extraordinary impacts. In this instance, a single report led to dramatic changes in public policy in both the UK and US affecting hundreds of millions of lives (one can only imagine the subsequent impact case study).

Whilst major publishers have moved to make much scientific and medical research relating to COVID-19 open access, calls for social research relating to the current crisis to be mobilized have been limited. As social research is relevant to so many aspects of the current crisis, there is thus a clear mandate for more of it to be made more readily available to the public and policymakers. However, opening up research is not enough on its own, and for social research to be more useful, much work needs to be done organizing and representing this expertise. Here there is a clear role for scholarly societies, research institutions and publishers. There is also a need to reconsider how social scientists can engage in the public sphere and how expertise, wherever it is found, can be represented coherently on social media platforms. One might also ask, where is the chief social scientific adviser to the government?

Practicing social science

Turning from an external to an internal perspective, COVID-19 threatens the actual practice of social science. There are clear ethical and safety concerns around carrying out forms of qualitative and engaged research at a time when social contact should be kept to a minimum. There are opportunities for some of these efforts to be redirected into different activities, such as revisiting datasets, refining methodologies and exploring distance approaches to collecting qualitative data. However, the implications for many research projects and researchers will be profound.

Further, social distancing is also affecting the dissemination and development of social research. As conferences, seminars and public events are cancelled, so are many of the informal mechanisms by which social research is communicated and made useful. Halted too is the cross pollination of ideas, serendipitous encounters and socialization that allows new ideas to come into being. Whilst it has been argued that a reduction in academic conferences and their related international travel is long overdue, these processes are not easily replicated in online environments, especially with little planning in the space of a few weeks. As social distancing distances social research from society, it also raises questions about research assessment and the need for exercises, such as REF 2021, when the current conditions are so exceptional.

The shift to remote working presents further challenges, diverting resources towards preparing online learning materials, placing an even greater burden on academic libraries to facilitate access to online resources. It also shatters the comfy illusion of the ivory tower, collapsing academic and domestic lives into one. As the pandemic develops, researchers will inevitably fall ill, be responsible for sick relatives and their local communities. It goes without saying, in such circumstances, undertaking social research is no longer a priority.

Ultimately the burden of this disruption to academic life will likely fall hardest on those who are least able to bear it. In the UK, where academics in all disciplines have recently been on strike, as many as two-thirds of researchers are employed on precarious, fixed-term contracts and are further supported by an army of PhD researchers and other casualized academics. Whilst funders and institutions have begun to release guidance in the face of the disruption, for those most at risk, let alone those without or between funder and institutional support, even mitigating measures will likely have serious consequences for their lives and careers.

Breaching everyday social science

As Graham Scambler has suggested, drawing on the ideas of Harold Garfinkel, the current COVID-19 pandemic serves as something close to a large-scale “breaching experiment.” Or an event that is so extraordinary that it serves to highlight the normally implicit and hidden structures that underwrite the smooth functioning of society. The same breaching of the everyday can be observed on a smaller scale in academia and the social sciences. As researchers socially distance themselves, events are cancelled and normal academic life grinds to a halt, it presents an opportunity to re-examine the everyday. Will the experience of remote working contribute to a greater recognition of the complex domestic social structures that sustain academic research? Will the pause on academic conferences and events lead to more serious engagement with open and online forms of research communication? Will the present dire need for social science expertise lead to a greater recognition of the profound and subtle ways in which social science contributes to society? Perhaps only time will tell, but the actions taken now may well define the future of the social sciences.