Compliance and Followership During COVID: Excerpt from ‘Together Apart’

COVID-19 has posed a significant challenge, with whole nations striving to coordinate their activities in response to the pandemic. In the process, it has been critical for people to follow advice and comply with policies in an effort to solve problems through effective forms of coordination and cooperation. In this chapter, we define compliance as a person’s acquiescence with a request (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004). The related, broader concept of followership (or following behaviour) refers to individuals’ actions in responding to leaders or to those in authority (Uhl-Bien et al., 2014). Here we explore a number of big questions about these processes. What drives compliance and followership? When do people choose not to comply with advice or regulations? What are helpful (and not so helpful) forms of followership?

In the context of the COVID-19 response, our answers focus on three key factors that drive compliance and followership: (a) the internalisation of collective concerns, (2) the behaviour of other members of people’s groups and communities, and (3) trust in government and its leaders.

Acts of followership are not individual in nature but result from the internalisation of collective concerns

There are a range of traditional ways of thinking about why people follow the instructions of others. One of the most influential of these argues that people have a strong and inherent tendency to ‘blindly’ follow the orders of leaders, particularly when those leaders are in positions of power. This analysis, which was famously set out by Stanley Milgram (1974) following his research into “Obedience to Authority”, suggests that people don’t think too much about why they are following, but do so mindlessly and instinctively. Another influential model suggests that followership is a matter of being “cut out” for particular follower roles, such that some people are engaged followers but others merely sheep (e.g., Kelley, 1988).

A problem with both these models, however, is that they fail to explain the importance of social context, and, in particular, the importance of the relationship between followers and leaders. If followership is a matter of being a particular type of person or of blindly following orders, why does one find the same person following some instructions vigilantly and ignoring others?

Looking at the evidence, we discover that contrary to Milgram’s claims, ordering people to do something generally fosters disobedience rather than obedience (Haslam et al., 2014). Indeed, unless people (a) see themselves as part of a larger collective ‘we’ (e.g., as ‘us New Yorkers’) and (b) identify with the cause of that collective, then they are unlikely to compromise on their personal self-interest (Haslam & Reicher, 2017). Accordingly, rather than ordering people to engage in particular behaviours (e.g., refraining from stock-piling scarce resources), it is generally more effective to request that they do so as part of an appeal to group-based sensibilities.

These observations are backed by evidence which suggests that people want to be respected and treated fairly in terms of a group membership that they share with policy makers (e.g., as Canadians, as Scots), and that if they feel that they are disrespected or treated unfairly, they are unlikely to fall in line (Tyler & Blader, 2003). Consistent with this, social identification with the authority or institution that applies a policy has been shown to underpin compliance with that policy (Bradford et al., 2015). Similar patterns have also been found for compliance with tax law (Hartner et al., 2010) and adherence to mandatory and discretionary rules set out by one’s employer (Blader & Tyler, 2009).

Compliance is shaped by perceptions of the behaviour of other members of our communities

People’s willingness to comply is also shaped by norms. These derive from our understandings of what other people — particularly those in the groups we identify with — think and do (Smith & Louis, 2008). Accordingly, communications about social norms can be used to influence and mobilise others (for good or bad; Cialdini et al., 2006; Fehr & Fischbacher, 2004; see Chapter 17). Indeed, there is evidence that perceptions of norms influence a range of citizenship behaviours including littering (Cialdini et al., 1990), recycling (Abbott et al., 2013), cooperation (Thøgersen, 2008) and compliance with tax law (Wenzel, 2004).

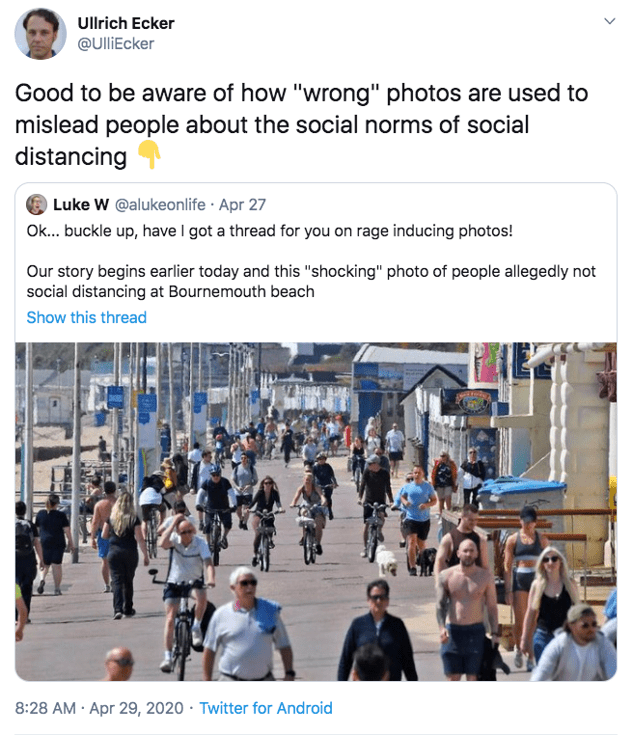

As the COVID-19 pandemic has unfolded, people’s cooperation with directives has been affected by the degree to which the behaviour in question was seen as both acceptable and widespread. By extension, this suggests that news reports that single out infrequent non-compliant behaviours can be problematic, because they suggest that non-compliant behaviour is prevalent and normative. For example, images of people apparently failing to practice physical distancing, or engaging in ‘panic buying’ can lead people to engage in these practices because they think that doing so is normative (see Figure 4). Ultimately, then, to foster compliance and followership it is useful for leaders to bolster their appeals to citizens by referring to other group members and invoking social norms, and, when they do, to craft these appeals in ways that foster cooperative forms of citizenship.

Trust in authorities can facilitate both healthy and fatal forms of followership

When the path ahead is complex and highly uncertain, a core ingredient of people’s willingness to follow leaders is their faith in those leaders and their actions. Accordingly, evidence indicates that trust in leaders and authorities is critical for leaders’ capacity to secure compliance with their policies (Jimenez & Iyer, 2016) and for encouraging followership more generally (Dirks & Skarlicki, 2004). But where does this trust come from?

The first thing to note is that the trust we have in leaders is not something that is fixed and immutable. Rather, like credit in the bank, it is something that is gained (or lost) over time as a function of leaders’ perceived contribution and service (or lack thereof) to the group they lead. More specifically, we trust a given leader to the extent that we see him or her as ‘one of us’ who is ‘doing it for us’ (Giessner & van Knippenberg, 2008; Platow et al., 2015).

But when people see their leaders as being ‘one of us’, this comes with some level of risk because it licenses leaders to take the group into uncharted terrain (Abrams et al., 2013). In the case of COVID-19, this license has been used to encourage both health-promoting and health-debilitating forms of followership. For example, trust in President Trump’s suggestion that one might use malaria drugs (or even household disinfectants; Rogers et al., 2020) to combat COVID-19 proved fatal for some of those who followed his advice (Waldrop, 2020).

On the other side of the ledger (and the planet), New Zealand’s Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern, delivered personable messages from her living room that showed her to be very much a ‘regular’ New Zealander (Roy, 2020) and thereby helped secure a high level of compliance with an extreme lockdown. Moreover, her message highlighted that the sacrifice she was asking New Zealanders to make was not for her, nor for themselves as individuals, but for the nation as a whole:

I have one final message. Be kind. I know people will want to act as enforcers. And I understand that, people are afraid and anxious. We will play that role for you. What we need from you, is support one another. Go home tonight and check in on your neighbours. Start a phone tree with your street. Plan how you’ll keep in touch with one another. We will get through this together, but only if we stick together. (Ardern, 2020) In this message, Ardern distils the essence of a social identity perspective on followership: recognizing that this is grounded in the strength of group-based ties between the leader and their group. Accordingly, her message focuses followers’ attention not on herself, but on the group and her commitment to it. This then encourages followers to do the same.

Explore the social influence chapters of Together Apart

Introduction to Social Influence

Leadership | S. Alex Haslam

The ultimate proof of leadership is not how impressive a leader looks or sounds, but what they lead others to do.

Compliance and Followership | Niklas K. Steffens

What drives compliance and followership? When do people choose not to comply with advice or regulations? What are helpful (and not so helpful) forms of followership?

Behaviour Change | Frank Mols

Social identity processes are a key source of human strength, and that leaders who tap into these are best positioned to drive the forms of behaviour change required to defeat COVID-19.

Conspiracy Theories | Matthew Hornsey

Conspiracy theories are often peddled by leaders and people in positions of authority with a view to shoring up support for a worldview which they represent and are seeking to advance.