The Virtue of Checking Documentation: You Never Know What You Will Find

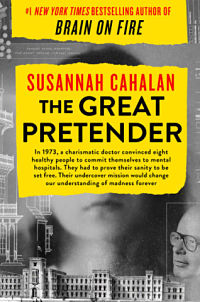

In The Great Pretender: The Undercover Mission That Changed Our Understanding of Madness (Grand Central, 2019), Susannah Cahalan describes her reinvestigation of one of the most famous and consequential experiments in the history of clinical psychology. In the January 19, 1973 issue of Science, professor David Rosenhan of the Stanford Department of Psychology published “On Being Sane in Insane Places,” an exposé revealing that psychiatric hospitals were incapable of distinguishing “the sane from the insane.”

Under Rosenhan’s direction, eight “pseudo-patients” had presented themselves for intake at various psychiatric hospitals, claiming that they heard voices saying “empty,” “hollow,” and “thud,” but experiencing no other symptoms. All eight were admitted for treatment, after which they reverted to their perfectly unafflicted selves. Nonetheless, seven of the pseudo-patients received diagnoses of schizophrenia (and the eighth was diagnosed with “manic depressive psychosis”). It took as long as 52 days for the pseudo-patients to be discharged, typically with an ominous notation of “schizophrenia in remission.”

The article’s impact was immediate and widespread, reinforcing public mistrust of psychiatry – in keeping with Erving Goffman’s ethnography Asylums – and spurring both the deinstitutionalization movement and a sweeping revision of psychiatry’s diagnostic categories. One result was the 1980 publication of the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, which sought to replace psychoanalysis with more scientific and determinative illness definitions. To this day, “On Being Sane in Insane Places” is one of the most frequently cited articles in the psychiatric literature, excerpted or summarized in most textbooks, and routinely assigned in both psychology programs and medical schools. The medical sociologist Andrew Scull referred to “On Being Sane in Insane Places” as “one of the most influential pieces of social science published in the 20th century.”

An experienced investigative reporter, and the survivor of a nearly tragic psychiatric misdiagnosis, Cahalan initially set out to amplify the Rosenhan study, not to debunk it. She was therefore shocked when she realized that much of the underlying data had been embellished, exaggerated, likely contrived, and very possibly fabricated.

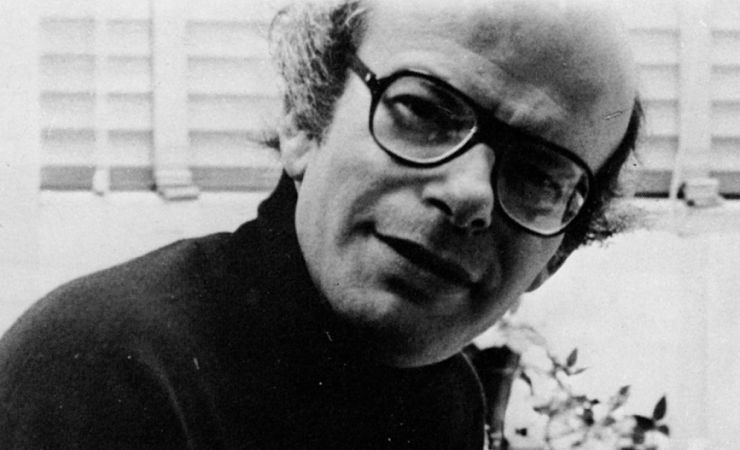

Having obtained access to Rosenhan’s notes, diary, and the 200-page manuscript of his unfinished book, Cahalan discovered that Rosenhan himself had been the first pseudo-patient, checking himself into Pennsylvania’s Haverford State Hospital under the name “David Lurie” at a time when he was teaching at Swarthmore College. The hospital intake notes, which Cahalan diligently tracked down, disclosed that Rosenhan/Lurie had feigned much more serious symptoms than were included in “On Being Sane in Insane Places.”

Far from claiming only a few mild auditory hallucinations, Rosenhan/Lurie told the admitting psychiatrist that he was able to intercept radio signals and listen to other people’s thoughts, which he muted by placing a copper pot on his head. He sought in-patient care because he believed that the hospital was better insulated than his home, where he had been unable to work or sleep. Rosenhan/Lurie found the situation so distressing that he had considered suicide. After admission, he continued to tell staff that the world might be better off without him, mumbling, twitching, and grimacing as he spoke. In other words, Rosenhan/Lurie had given the hospital every good reason to admit and treat him; it would have been malpractice simply to send him home. None of the most significant details had been included in the incendiary Science article, however, which instead implied utter cluelessness, if not outright disregard, by the staff psychiatrists.

Perhaps even more troubling, Cahalan also learned that Rosenhan had suppressed information that was contrary to his argument. Shoe-leather reporting led her to the home of a ninth pseudo-patient, a former graduate student at Stanford, who had actually received excellent in-patient care at a California mental hospital. Rosenhan’s response to the inconvenient data was to excise the subject from his study. The only reference to pseudo-patient nine was buried in a footnote, falsely claiming that he had violated the study’s protocols.

In all, Cahalan was able to identify three of the nine possible pseudo-patients. She expressed considerable doubt as to whether the other six ever existed, as there was no concrete information about them in any of Rosenhan’s notes.

The Rosenhan revelations provide a valuable lesson for other social scientists. You never know what you will find once you begin fact-checking sources against available documentation. The admitting psychiatrist at Haverford Hospital obviously had no reason to think that he was evaluating a pseudo-patient, much less that his medical history would someday be part of an iconic psychology article, and then a debunking investigation. He therefore had no motive to exaggerate or misreport Rosenhan/Lurie’s presenting symptoms. A physician’s notes are not invariably accurate, of course, but in this instance they are obviously preferable to Rosenhan’s own account of the initial interview, given his interest in telling a publishable story about David Lurie’s encounter with psychiatry.

Rosenhan turns out to have been his own source for the first vignette in the Science article, but Cahalan did not know that when she began searching through the documentation. She only knew that she needed to check every available record if she wanted to write an accurate book. That is also why journalists, historians, biographers, and other non-fiction narrators routinely consult documentation to confirm, test, or otherwise assess the trustworthiness of their sources and informants. You would think the same would be true of ethnographers who collect and report information from research participants whose reliability is necessarily affected, for better or worse, by all the factors that can influence human communication and memory. Alas, that is not always the case.

It is frankly surprising that so many sociologists have recoiled from my proposal, in Interrogating Ethnography (Oxford, 2017), that “informants’ statements should be verified and documented whenever possible.” Prominent skeptics of documentation – including Michael Burawoy, Mikaila Mariel Lemonik Arthur, and Paul Atkinson – have been unwilling to accept my rather modest observation that written records, although not always accurate, may sometimes have certain advantages over human memory. Speaking about legal records, Texas Christian University’s Jeff Ferrell said, “as for their usefulness in fact-checking what ethnographers find or hear on the street, I’d say minimal at best.”

To be sure, many outstanding ethnographers have, in contrast, made a practice of comparing their informants’ narratives to available documentation. As I noted in Interrogating Ethnography, Matthew Desmond engaged in extensive fact-checking for his Pulitzer Prize-winning book Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City (Crown, 2016). More recently, Forrest Stuart made a point of checking his “participants’ words” with “documentary sources, and other forms of external verification” for Ballad of the Bullet: Gangs, Drill Music, and the Power of Online Infamy (Princeton, 2020, pp. 209-10).

The Rosenhan paper is not the only well-known social science study to have been shaken by after-discovered documentation. Both Philip Zimbardo’s Stanford prison experiment and Stanley Milgram’s Harvard study of obedience to authority were at least partially discredited when researchers examined the underlying records. Similar issues have been identified in fields ranging from primate cognition to food science. Given the replication crisis lately identified in social psychology, it is impossible to know how many prominent, or not so prominent, social science publications have been based inaccurate, overstated, or even falsified observations or other data.

It takes an impressive leap of faith to believe that ethnography has had no such problems – if not rising to the level of data manipulation, then certainly in the form of misleading, deceptive, or disingenuous information from research participants – especially since the methodology lacks most of the nominal safeguards present in other research. As Stuart notes, “ethnographies are typically conducted by lone researchers, who are singularly empowered to collect data, analyze patterns, and write up findings (209).” Moreover, most ethnographies are heavily anonymized, with even the research sites obscured or masked, and field notes sequestered, thus making reassessment, much less replication, difficult or impossible.

Given the consequent risk of reliance on “rumor, shaky recollections, and half-truths,” as Stuart puts it (210), ethnographers ought to welcome third-party attempts at verification or disconfirmation, which is a standard expectation in most disciplines. Regrettably, the opposite has often been the case. Many ethnographers have responded to outside critique, including mine, with a combination of rationalization, defensiveness, and deep denial. Rather than reexamine the potential pitfalls of the ethnographic method, some sociologists have instead questioned the motives and good faith of critics – a deflection that is almost always an indication of substantive weakness.

As the work of Cahalan and others demonstrate, however, no academic project can ever be assumed free from inaccuracies or faults. True scholarship therefore requires a vigorous dialectic, including a review of both internal and external documentation. Anything less is simply an invitation to error.

![Share Your Most Surprising Policy Citation for Chance to Win $500 [Closed] Share Your Most Surprising Policy Citation for Chance to Win $500 [Closed]](https://www.socialsciencespace.com/wp-content/themes/conferpress/images/default_thumbnail-new-border.jpg)