Does the Cost Point Influence Your Idea of the Larger Point of University Itself?

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought the university sector under greater scrutiny. In some cases, this has prompted new conversations about the purpose of higher education. These have included the extent to which universities are upholding their commitment to public service, and whether the current institutional adjustments in universities will change the way higher education is delivered.

But what do students themselves think about what university is for? In 2017-18, my colleagues and I asked 295 students across six European countries – Denmark, England, Germany, Ireland, Poland and Spain – about what they believed to be the purpose of university study. Their responses shed light on the possible future of higher education in Europe.

This research, which forms part of the Eurostudents project, investigates how undergraduate students understand the purpose of higher education. We found that for many students, it serves three particular functions: to gain decent employment, to achieve personal growth, and to contribute to improvement in society.

But there were interesting variations in students’ views, which often corresponded to how much they had to pay for their studies.

The career ladder

The most common purpose of higher education that students spoke about was to prepare themselves for the labour market. Some students stated that a degree was essential to avoid having to take up a low-skilled job. However, many students believed that an undergraduate degree was insufficient for highly skilled or professional employment.

Here, we see a shift from a conception of higher education as an investment to help move up a social class to viewing it as insurance against downward social mobility.

As a student in England said:

“I don’t really think there’s much of an option. If you want to get a decent job these days, you’ve got to go to university because people won’t look at you if you haven’t been.”

There were some differences across countries. Emphasis on the purpose of university education being preparation for the job market was strongest in the three countries in our sample where students had to make greater personal financial contributions: England, Ireland and Spain.

Personal growth

The students in our study also discussed ideas of personal growth and enrichment. This was the case in all six countries, including in England where the higher education sector is highly marketized. This means it is set up as a competitive market, where students pay tuition fees and are protected by consumer rights legislation, while metrics such as league tables encourage competition among institutions.

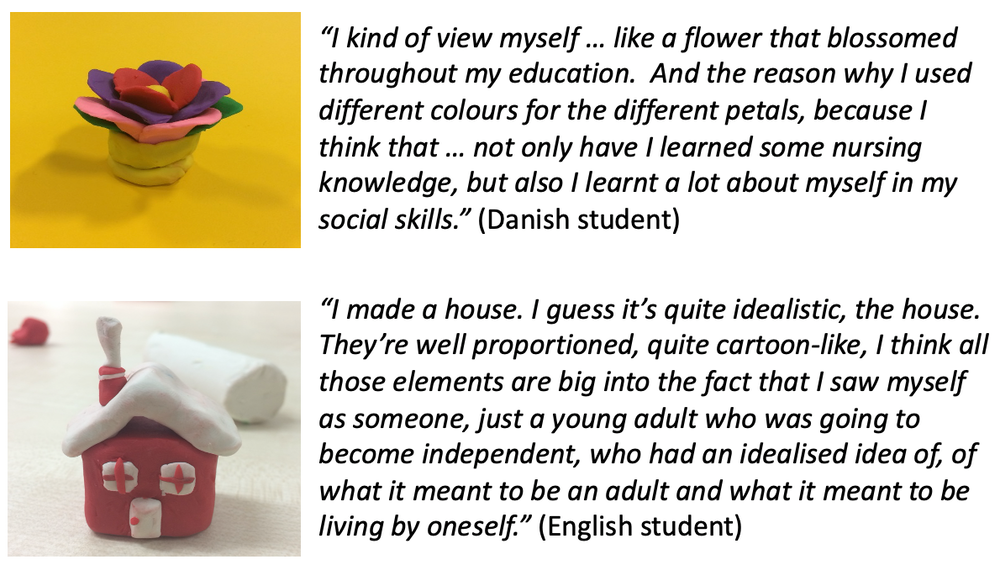

Some students emphasized how they were “growing” through the knowledge they were gaining. Others placed more emphasis on aspects of wider learning that they had experienced since embarking upon their degree. This included interacting with a more diverse group of people than they had previously, and having to be more independent.

Students in Denmark, Germany and Poland talked about this kind of growth – which happened outside formal classes – more frequently than students in the other three nations. Notably, in these countries, students make less of a personal financial contribution to the cost of their university study. When this purpose was mentioned by English students, it was associated particularly with learning how to live independently.

Societal development

Students in all six countries talked about how higher education could improve society. This was brought up most frequently in Denmark, Germany and Poland – where students receive greater support from the government and make less of a personal financial investment to their university education than in the other countries in our sample.

Students tended to talk about their contribution to society by attending university in one of three ways: by contributing to a more enlightened society, by creating a more critical and reflective society, and by helping their country to be viewed more competitively worldwide.

A Polish student said:

“[University education is critical to] shaping a responsible and wise society … one which is not blind, which will do as it is told.”

Meanwhile, a Danish student commented:

“We’re such a small country, we have to do well … we have to do better because there are so many people around the world … we have to work even harder to compete with them.”

Only Danish and Irish students spoke about national competitiveness in this way. This is likely to be linked to specific geo-political and economic factors, particularly the relatively small size of both nations when compared to some of their European neighbors and the structure of their labor markets.

It is unsurprising to find that many students across Europe believe that a key purpose of university study is to equip them for the job market, as this is often the common message given by governments.

Nevertheless, as shown here, many students have broader views. They see the value of higher education in promoting democratic and critical engagement, while also furthering collective, rather than solely individual, ends.

The national variation we found also suggests that the enduring differences in funding across the continent may affect on how higher education is understood by students.

This post draws on the author’s co-authored article, “Students’ views about the purpose of higher education: a comparative analysis of six European countries,” published in Higher Education Research and Development.