Our Study Finds Women Are Better at Statistics Than They Think

The big idea

Women in statistics classes do better academically than men over a semester despite having more negative attitudes regarding their own abilities, according to our recent study in the Journal of Statistics and Data Science Education.

Using data from more than 100 male and female students from multiple statistics classes, my colleague and I assessed gender differences in grades over the course of a semester. As part of the study, students also answered surveys at the start and end of the semester that measured six different things: their fear of statistics teachers in general; their thoughts about the usefulness of statistics; their perceptions of their own mathematical ability; their anxiety in taking tests; their anxiety in interpreting statistics; and their fear of asking for help.

Overall, we found that students with more negative perceptions of their own mathematical ability had lower grades over the course of the semester. What’s even more interesting are the gender differences that emerged.

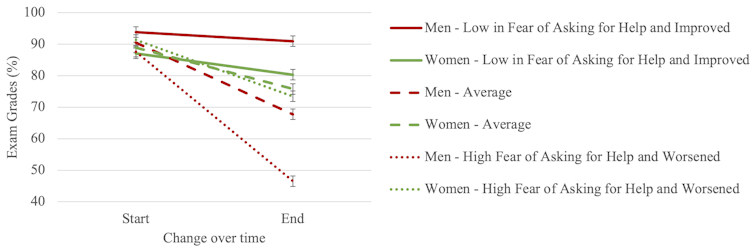

Even though men and women scored similarly on exams at the start of the semester, women finished the semester with almost 10 percent higher final exam grades. This was the case even though women had significantly worse attitudes about their mathematical abilities at the start of the semester than their male counterparts.

At the beginning of the semester specifically, women were more likely to rate their mathematical abilities as lower than men in the class and report more anxiety toward exams and toward interpreting statistical findings. However, each of these self-assessments improved over the course of the semester such that women’s attitudes didn’t differ from men’s by the end.

Meanwhile, the grades of male students who reported fear of statistics teachers or fear of asking for help decreased more sharply over the course of the semester. For men whose attitudes improved during the semester, grades also improved – though not as much as women’s grades improved.

Why it matters

A number of studies have shown that from an early age, boys and girls learn math equally well.

However, girls are less likely to be called on in math classes than boys, even when they raise their hands as much as boys do. Moreover, some teachers unconsciously grade girls’ math tests more harshly than boys’. By middle school, gender differences in math scores emerge. These factors may contribute to adult women’s being more likely to rate themselves as less mathematically skilled than men. As a result, women are also less likely to pursue STEM – science, technology, engineering and math – occupations.

The results from our study, in line with others, bolster the notion that women have the potential to do as well as men, and even better, in STEM fields, such as statistics. We contend that women would benefit from additional mentoring to encourage them as they begin pursuing STEM-related education.

What still isn’t known

The evidence above provides hints at some of the causes of the gender discrepancy in perceived ability. However, there is much we still don’t know.

For example, why did the attitudes of the women in our study improve over time? Was it based on their confidence in their abilities as their grades improved, or did their statistics teachers influence their perception of their own abilities over time?

More research is needed to understand exactly how women differed from men in their attitudes over the course of the school semester, among other questions. In particular, we’d like to disentangle exactly which classroom or instructor factors can lead to better attitudes among students, ultimately translating to better grades.