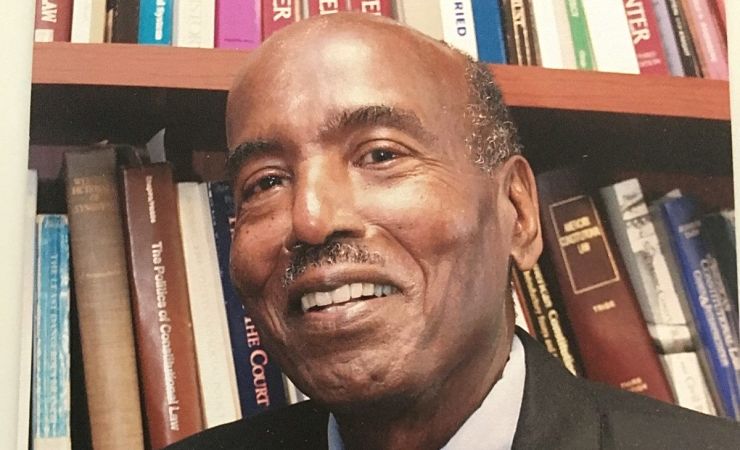

A Giant in Mentoring Political Leaders: Lucius Barker, 1928-2020

Political scientist Lucius Barker, a pioneering African-American academic whose influence in fields like constitutional law and civil liberties has been amplified by the high-profile leaders he mentored, died on June 21. He was 92.

Barker, the William Bennett Munro Professor of Political Science at Stanford University from 1990 until 2006, taught such future leaders as twins Joaquin Castro (now a congressman from Texas) and Julián Castro (former U.S. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development); Cory Booker (now a senator from New Jersey); and Tony West (former U.S. associate attorney general).

“Professor Barker was more than a professor to me. He was a model and an inspiration,” Booker was quoted in a release from the Midwest Political Science Association. “He taught me the importance of rigorously pursuing knowledge, and using that knowledge in the service of others. And he lived this ethos, with a generosity of heart that nurtured, encouraged, and guided me toward a career of public service. He was indeed one of life’s great professors.”

Barker – along with his older brother Twiley – figured prominently in the academic world of political science even as non-white faces were rare. In 1992 he became just the second black man to serve as president of the American Political Science Association (Ralph Bunche had been president 39 years before).

Lucius Jefferson Barker was born on June 11, 1928, the fifth of six children born to school teachers in Franklinton, Louisiana. Lucius was named for his uncle, a doctor, and when he started his college career at Southern University and A&M College in Baton Rouge he entered as a promising pre-med student. But as a sophomore he – and Twiley, attending on the GI Bill alongside Lucius — were seduced by a political science course taught by freshly minted PhD Rodney Higgins. (Higgins proved an inspiration to a number of future prominent political scientists, foreshadowing the Barkers’ own impact.)

Speaking years later with the APSA/Pi Sigma Alpha: African American Political Scientists Oral History Project (from which many of his personal recollections cited below are drawn), Barker described the process of decoupling from pre-med:

[Higgins] had a lot of students in his class. And while taking his class, we were also taking one of our other prerequisites for pre-med, which was comparative anatomy. … [C]omparative anatomy was taught by a person whom I was not particularly fond of, but more than that, I didn’t like the smell of the formaldehyde and all that kind of stuff, the dissecting of frogs and stuff like that. I thought it was repulsive. And, at the same time you have those two things vying for your attention — this guy who was very suave and good, teaching American politics, and there was the other guy who was not that good.

Lucius Barker received his bachelor’s in political science 1949. He attended the University of Illinois Urbana/Champaign for master’s work on constitutional law and civil liberties. Twiley had entered that university the year before and, as Lucius later said, had already shown that graduates of historically black colleges were the scholarly equal of whiter schools’ graduates. Not that a little innocent subterfuge didn’t help at times.

“Most people didn’t know where Southern University was,” he explained to the oral history interviewer. “They thought when you said, ‘I went to Southern,’ they thought you meant Southern Illinois. So you were at the University of Illinois, see, and they thought you were talking about SIU.”

Barker thrived at the University of Illinois, and became the first black graduate teaching assistant in the College of Arts and Sciences. He recalled being summoned by the chair of his department, Charles M. Kneier, who made the teaching offer. Kneier was frank but hopeful, Barker would recall. “In that time, the 1950s, there might be some students who had a few problems with that [honor being shown Barker] and he didn’t think so, but he wanted to let me know that the department was fully aware, the university was fully supportive, and he was confident that I would do OK and so forth and so on. I walked out of his office sky high.”

After receiving his master’s (1950) and PhD (1954) from Illinois, Barker took a job back at Southern (as would Twiley), where he taught alongside Higgins. But Southern focused on teaching, not research, and after a year and half, Barker said, “I saw myself slipping in terms of what I really wanted to do in terms of any kind of research possibility of the program.” It was a tough decision, one made harder when figures like Lionel Newsom pressured him to stay “where he was needed” teaching black students in the Jim Crow South.

But leave he did, taking a position at the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee, an urban campus with a rising reputation and where Barker would spend11 years. Barker took a leave in 1964 to serve as a Liberal Arts Fellow of Law and Political Science at the Harvard Law School. (“And it was during that year,” Barker noted, “that I did get married and my wife said, ‘You had to go to Harvard Law School to learn how to propose to me.’”)

In 1967 Barker returned to the University of Illinois as assistant chancellor, staying there two years before he was lured to Washington University in St. Louis to teach and chair the political science department. He stayed at Washington until 1990, when he headed to Stanford, where he would also serve a stint as department chair.

“Lucius J. Barker was a giant in the field of political science,” said Paula D. McClain, current president of the APSA. “Yet, despite his eminence, Lucius was a generous and selfless human being who mentored numerous young scholars of all races, providing them opportunities to achieve their scholarly potential.”

Barker wrote prolifically. In 1970 he and Twiley published Civil Liberties and the Constitution, which is now in its ninth edition. “We tried,” Lucius would tell the Chicago Tribune, “to make it come alive, to let people know that court cases don’t just spring out of nowhere.” In 1976 he co-authored a defining book on systemic racism, Black Americans and the Political System, which evolved over four editions into African Americans and the Political System.

Not all his books were aimed at the academy. After serving as a delegate at the Democratic National Convention for Jesse Jackson’s 1984 presidential campaign, Barker wrote Our Time Has Come: A Delegate’s Diary of Jesse Jackson’s 1984 Presidential Campaign. “Dr. Barker’s book on my 1984 presidential campaign, and his work overall, will remain crucial in understanding how racial groups can mobilize and drive meaningful change,” Jackson said, adding, “It’s fitting to salute Lucius Barker during this crucial time in race relations, as he was a scholarly soldier in our ongoing battle for equal rights.”

Barker had been involved in other campaigns as an activist and observer, ranging from John F. Kennedy’s in 1960 to Barack Obama’s in 2008.

Before heading APSA, Barker served as president of the Midwest Political Science Association in 1984, and in 1989 was the founding editor of the National Political Science Review. The review, which became the National Review of Black Politics last year, is published by the National Conference of Black Political Scientists; Barker was president of the conference, which was founded at Southern, in 1983-84. In 1994 he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Barker died in his Menlo Park, California home due to complications from Alzheimer’s disease. His wife Maude had died 33 days earlier. Twiley Barker died in 2009.

For more on the Barkers

Interview with Lucius J. Barker, April 19, 1991 | APSA/Pi Sigma Alpha: African American Political Scientists Oral History Project

Interview with Twiley W. Barker, July 25, 1991 | APSA/Pi Sigma Alpha: African American Political Scientists Oral History Project

A virtual celebration honoring the legacy of Lucius J. Barker is scheduled for July 11, 2020