Blessed are the Trusting, For They Are More Likely to Vote

Forecasting election results is hard. Predicting who will turn out to vote in the United States is not.

The rich are more likely to vote than the poor. The better educated are more likely to vote than the less educated. White people are more likely to vote than racialized Americans.

As a scholar who has studied trust and how it matters for years, I can say that generalized trust — an expectation of good will and benign intent of others — is also a powerful predictor of voter turnout.

Whomever they vote for, Americans who are trusting are more likely to have either cast their ballots already or will on election day than Americans who do not trust easily.

Trust inequality can explain disparity in voter turnout. My research shows that, regionally across the United States, trust is lower in the South, and Southerners are less likely to vote. I also show that those who feel they have less power in society are less able to trust. This can, at least partly, explain why the poor and racialized Americans are less likely to vote.

The promise of democracy in part rests on citizens being able to trust equally.

Post-election data

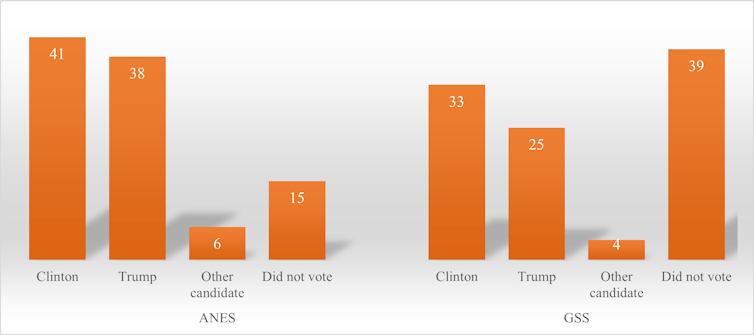

My study of elections relies largely on turnout data from post-election surveys. Two major ongoing surveys that document voter turnout in the U.S. are the American National Election Studies (ANES) and the U.S. General Social Survey (GSS).

Since 1948, the ANES has asked respondents after each presidential election whether they voted. The mission of the ANES data is to provide high-quality data to help researchers understand “why does America vote as it does on election day.”

The GSS has interviewed American citizens — annually from 1972 to 1993 and biannually since 1994 — to ask similarly whether they voted in presidential elections. See the turnout information from the 2016 presidential below:

Data from the U.S. Census Bureau shows that 61.4 percent of the voting-age population reported voting in the 2016 presidential election. In comparison to this number, the graph above shows the ANES significantly overestimated voter turnout at 85 percent.

That’s not unusual. Post-election surveys often overestimate voter turnout due to reasons that include social desirability response bias (the tendency of survey respondents to answer questions in a manner that will be viewed favourably by others), recall errors (the gap grows as more time passes between the election and the survey interview) and biased non-response (people who do not vote are especially unlikely to participate in surveys).

Nonetheless, these post-election surveys are useful for studying, for example, how race, gender and socioeconomic class might shape voting behaviour, so I’ve included data from both surveys in my research.

Trusting Americans are more likely to vote

Previous research has also suggested that trust plays an important role in political participation. Voting is a typical form of political participation. That means we would expect voter turnout to be higher among Americans who trust than those who do not trust easily.

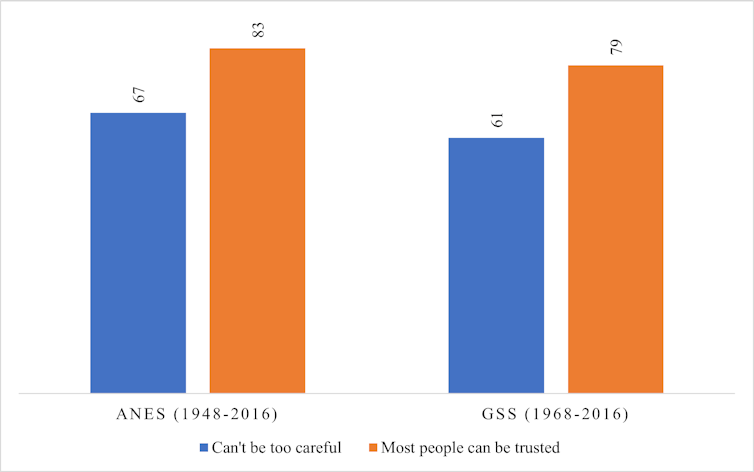

In many surveys, the widely used statement to measure overall trust is: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you cannot be too careful in life?” This statement was part of both the the ANES and the GSS surveys.

My analysis of the data from both surveys shows that Americans who think “most people can be trusted” are much more likely to vote than those who think “cannot be too careful in life.” The pattern is also highly consistent when I separate the analysis on a yearly basis. Higher trust is associated with a higher turnout in every U.S. presidential election since 1948.

Taking into account race, gender, age, level of education and household income, as well as the year of the election, Americans who trust are about 70 percent more likely to vote than those who do not trust, regardless of which survey we use (72 percent from ANES; 70 percent from GSS).

Trust impacts Republicans more than Democrats

But does trust affect Republican voters and Democrat voters differently?

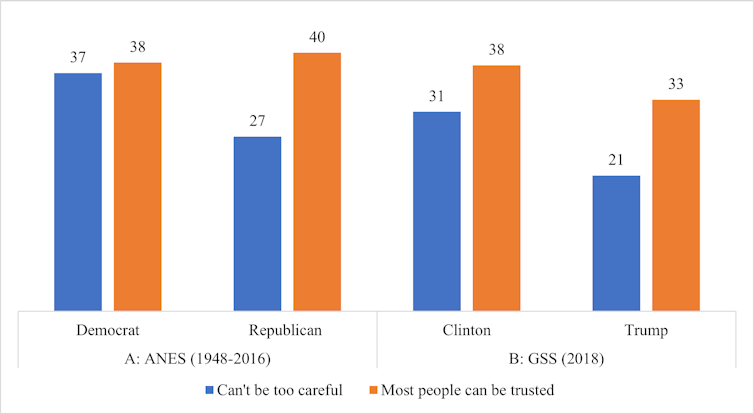

To answer this question, I compare turnout gaps between “trusters” and “mistrusters” among Republican voters and Democrat voters.

The graph below shows that overall the voting gap between trusters and mistrusters is greater among those who vote Republican than those who vote Democrat. Specifically, based on the cumulative data from the ANES (1948-2016), the left side of the graph shows that while the voting gap between trusters and mistrusters is only about one percentage point (38 percent versus 37 percent) for Democratic voters, the gap is 13 percentage points for Republican voters (40 percent versus 27 percent).

The right side of the graph focuses on the 2016 election only using data from the 2018 GSS. It shows that while the voting gap between trusters and mistrusters was seven percentage points among Clinton voters, the gap was 12 percentage points among Trump voters.

These findings suggest trust has a greater impact on Republican voters than those who vote Democrat.

Why are minorities less likely to vote?

Racialized Americans are often found to have a low voter turnout. The Pew Research Center has reported that the turnout rate in the 2016 presidential election was 65.3 percent among white registered voters, 59.6 percent among Blacks, 49.3 percent among Asians and 47.6 percent among Hispanics.

Common explanations for why minorities are less likely to vote include voter suppression and systematic discrimination. However, in his recent book The Turnout Gap, political scientist Bernard Fraga has argued instead it’s the sense of political inequality that largely explains the majority-minority gap in turnout.

Turnout gaps

Trust is associated with control, political efficacy and sense of political empowerment. Can minorities’ lower trust explain their lower turnout?

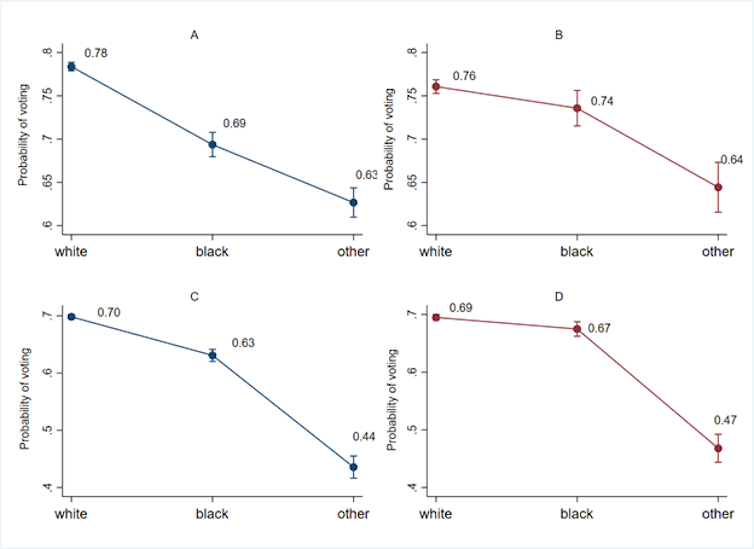

To show how trust can help explain the turnout gap across racial groups, I estimate the average probability of voting for white people, Black people and other racialized Americans using data from both surveys. The base model includes race and year variables, while the second model adds a trust variable to the base model. Here’s a visualization:

Graph A shows that the average turnout rate among white voters over an 18-year span is 78 percent, 69 percent among Black voters and 63 percent among other racialized Americans.

When taking into account the trust differences among these groups, these numbers become 76 percent, 74 percent and 64 percent respectively (Graph B). In other words, the relative gaps in turnout have become significantly smaller. For example, the gap between white voters and Black voters in Graph A is nine percentage points, but after controlling for trust, it’s only a relatively insignificant two percentage points. These findings are based on the ANES data.

Replicating the analysis using data from the GSS shows a consistent pattern. See Graphs C and D.

What does this show us in broader terms?

Democracy only works well when citizens participate in the democratic process and participate equally. But in the United States, lack of trust is eroding democracy’s promise.